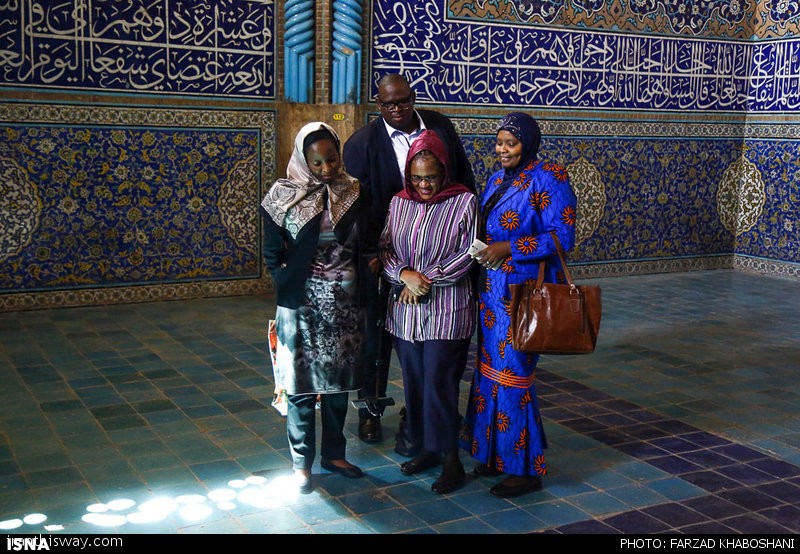

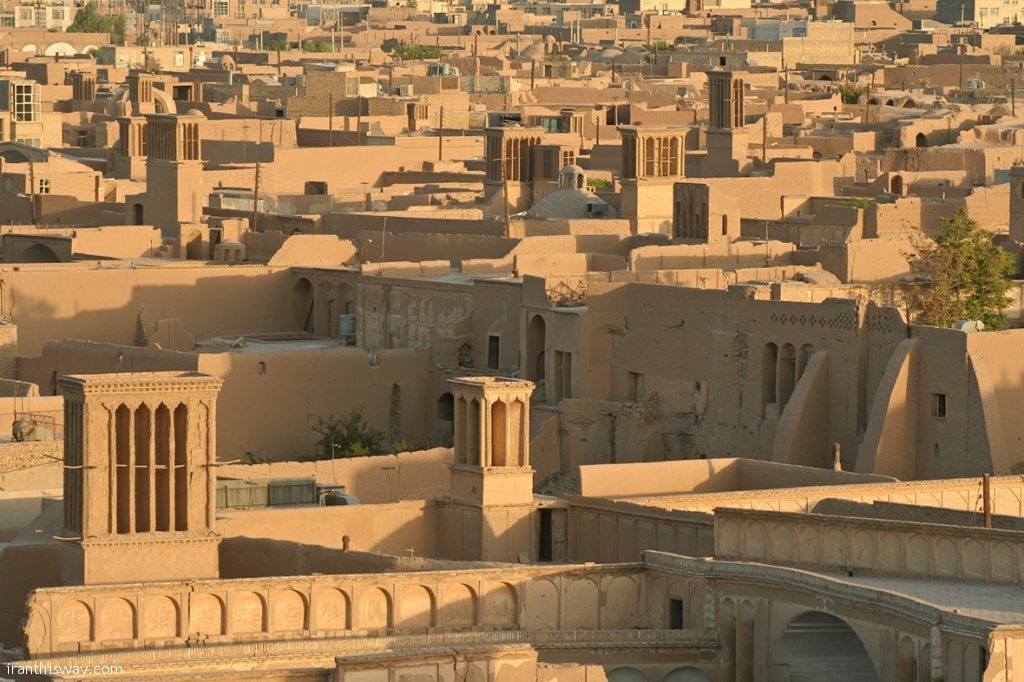

Kind women of Shahsevan nomadic tribes play key role in the economic life of their community, usually hosted by Sabalan outskirts during spring and summer. Photo: MNA

SHAHSEVAN (Šāhsevan), name of a number of tribal groups in various parts of northwestern Iran, notably in the Moḡān and Ardabil districts of eastern Azerbaijan and in the Ḵaraqān and Ḵamsa districts between Zanjān and Qazvin. Most of the latter groups also originated in Moḡān (see DAŠT-e MOḠĀN), where Shahsevan ancestors were located during Safavid times.

The Shahsevan traditionally pursued a nomadic pastoral way of life, migrating between winter pastures near sea-level in Moḡān and summer quarters 100-200 km to the south on the Sabalān (or Savalan) and neighboring ranges, in the districts of Ardabil, Meškin, and Sarāb. The nomads formed a minority of the population in this region, though, like the settled majority, whom they knew as Tāt, they were Shiʿi Muslims, and spoke Turkish.

Unlike the Baḵtiāri and the Qašqāʾi of the Zagros, the Shahsevan lived in an accessible and much-frequented frontier zone. The fertile Moḡān steppe, extensively irrigated in mediaeval times, was the site chosen by Nāder Shah Afšār (in 1736) and Āḡā Moḥammad Khan Qajar (in 1796) for their coronations. Shahsevan summer pastures, surrounded by rich farmlands, lay between Ardabil, a historically important shrine city and trade centre, and Tabriz, capital of several past rulers. Grain, fruit, wool and meat from the region have long been widely marketed. Raw silk produced in the neighboring provinces of Gilān and Shirvan figured prominently in international trade passing through or near Shahsevan territory. Control of these resources was a major motivation for conquest: since the 16th century, Persian, Ottoman, and Russian and Soviet forces claimed or occupied Shahsevan territory on several occasions each. In such a location, Shahsevan relations with governments have taken a different course from those of the Zagros tribes.

Origins and history. Shahsevan history since the early 18th century is fairly well documented, but their origins remain obscure. Turkic identity and culture are overwhelmingly dominant among them, though the ancestors of several component tribes were of Kurdish or other origins. Apart from their frontier location and history, they differ from other nomadic tribal groups in Iran in various aspects of their culture and social and economic organization. Most distinctive is their tent-hut, the hemispherical, felt-covered alačıq. This dwelling and other cultural features can be traced to the Ḡozz Turkic tribes of Central Asia that invaded Southwest Asia in the 11th century C.E.

The Shahsevan were a collection of tribal groups brought together in a confederacy some time between the 16th and the 18th centuries. Most discussions of the term Shahsevan refer to its original meaning as extreme personal loyalty and religious devotion to the Safavid kings.

By the 20th century, the Shahsevan had acquired three rather different versions of their origins. The best known is that they were a new tribe formed as part of the military and tribal policies of the Safavid rulers. This is based on a passage in Sir John Malcolm’s History of Persia (London, 1815, I, p. 556), to the effect that Shah Abbas I (1587-1629) formed a special composite tribe of his own under the name of Shahsevan, in order to counteract the turbulence of the rebellious qezelbāš chiefs, who had helped his ancestor Shah Esmāʿil to found the Safavid dynasty a century earlier. Vladimir Minorsky, in his article “Shāh-sewan” in EI1, noted that “the known facts somewhat complicate Malcolm’s story” and that the references in contemporary Safavid chronicles did not amount to evidence that “a single regularly constituted tribe was ever founded by Shāh ʿAbbās under the name of Shāh-sewan.” In later readings of Malcolm’s account, the Shahsevan appear as a personal militia, a royal guard, and there is some evidence for the existence of a military corps named Shahsevan in the mid-17th century.

Minorsky drew attention to the writings of several Russian officials who recorded the traditions of the Shahsevan of Moḡān with whom they were in contact during the 19th century. These traditions, which differ from but do not contradict Malcolm’s story, vary in detail, but agree that Shahsevan ancestors came from Anatolia, led by one Yünsür Pasha. They present the Shahsevan tribes as ruled by paramount chiefs (elbey/ilbegi) descended from Yünsür Pasha, and as divided between chiefly beyzadä (beg-zāda; descendants of the original immigrants) and commoners (hampā or rayät/raʿiyat). They refer to an original royal grant of pastures in Ardabil and Moḡān, and to the contemporary royal appointment of the chiefs. These legends, presumably originating with the chiefs, legitimate both their authority over the commoners and their control of the pastures, the most important resource for all their nomad followers. This writer heard similar legends in the 1960s from descendants of former elbeys.

This second version of Shahsevan origins gave way in the 20th century to both the first version and a third, commonly articulated among the ordinary tribesmen and in modern writings on them. In the third version the Shahsevan are thirty-two tribes (otuz-iki tayfa/ṭāyefa), all of equal status, and no mention of paramount chiefs is made. The basis of this story is obscure, but it may refer to the presumed origin of the Shahsevan from among the 16th-17th-century qezelbāš tribes, which in some accounts also numbered thirty-two.

Safavid sources published to this date provide no historical evidence for Malcolm’s story, which is based on a misreading of chronicle sources. Nevertheless, most historians, Iranian and foreign, have adopted it, and it has been assimilated through modern education into Iranian and even current Shahsevan mythology. Among recent writers on the Safavids, only a few acknowledge the doubts about Malcolm’s story; some refrain from comment on Shahsevan origins, others, while referring to Minorsky’s and sometimes this writer’s investigations, ignore the conclusions and reproduce the old myth as historical fact (see Tapper, 1997, pt. I).

Neither the first nor the second versions of Shahsevan origins can be fully documented. Sixteenth-century sources do record tribal groups and individuals in the Moḡān region bearing the names of later Shahsevan component tribes. By the late 17th century the name Shahsevan, often as a military title in addition to qezelbāš tribal names such as Afšār and Šāmlu (and Šāmlu components such as Beydili/Begdeli, Inallı/Ināllu, Ajirli/Ajirlu), is associated with Moḡān and Ardabil. Other prominent tribes in the region were the qezelbāš Takile/Tekeli, and the Kurdish Šaqāqi and Moḡāni/Moḡānlu. But there is no firm evidence of a unified Shahsevan tribe or confederacy as such until the following century.

In the 1720s, with the rapid fall of the Safavid dynasty to the Afghans at Isfahan, and Ottoman and Russian invasions in northwest Persia, for several crucial years Moḡān and Ardabil were at the meeting point of three empires. The tribal groups of this frontier region were thrust into a political role for which they would have been ill-prepared by decades of peace. Records for those years, the first that mention Shahsevan activities in any detail, depict them as loyal frontiersmen, struggling to resist the Ottoman invaders and to defend the Safavid shrine city of Ardabil, especially in the campaigns of 1726 and 1728. Ottoman armies crushed the Šaqāqi in Meškin in autumn 1728, and then in early 1729 cornered the other tribes in Moḡān. Leaving the Ināllu and Afšar to surrender to the Ottomans, the Shahsevan and Moḡānlu crossed the Kura/Kor river to Salyan to take refuge with the Russians, under the leadership of ʿAliqoli Khan Shahsevan, a local landowner.

When Nāder Shah Afšār recovered the region in 1732, the Shahsevan and Moḡānlu returned to Iranian sovereignty. The Šaqāqi, Ināllu and Afšār who had been defeated by the Ottomans were among numerous tribes Nāder exiled to his home province, Khorasan. After his death (1747), the Šaqāqi returned to settle around Miāna, Sarāb, and Ḵalḵāl, and the Ināllu and Afšār (both now bearing the name Shahsevan too) to the Ḵaraqān, Ḵamsa, and Ṭārom regions south and southeast of Ardabil. One of Nāder’s assassins, Musā Beg Shahsevan, was apparently from the Afšār who settled in Ṭārom.

Nāder Shah seems to have formed the tribes remaining in Moḡān and Ardabil into a unified and centralized confederacy under Badr Khan Shahsevan, one of his generals in the Khorasan and Turkestan campaigns. Possibly son of ʿAliqoli Khan, Badr Khan is linked by the later traditions with Yünsür Pasha, and his family, the Sarı-ḵanbeyli (Sāru-ḵānbeglu), probably came from the Urmia Afšārs. Shahsevan chiefly tribes such as Qojabeyli, ʿIsālı, Balabeyli, Mast-ʿAlibeyli, ʿAli-Babalı, Polatlı, Damirčili, traced cousinship with the Sarı-ḵānbeyli Afšār. Many of the commoner tribes (such as Ajirli and Beydili) bear names indicating Šāmlu origins.

In the turbulent decades after Nāder’s death, Badr Khan’s son (or brother?) Nażar ʿAli Khan Shahsevan governed the city and district of Ardabil. Shahsevan khans participated actively in the political rivalries and alliances of the time, involving the semi-independent neighboring khans of Qara Dagh, Qara Bagh, Qobba, Sarāb and Gilān, the Afšār, Afghan, Zand, and Qajar tribal rulers of Iran, and agents and forces of the Russian Empire. By 1800 the Sarı-ḵānbeyli family had split, dividing the Shahsevan into two confederacies, associated with the districts of Ardabil and Meškin.

Under the early Qajars, the two wars with Russia raged across Shahsevan territory and resulted in the loss of the best part of their winter quarters in Moḡān, and considerable movements of tribes southwards. The khans of Ardabil, notably Nażar ʿAli Khan’s (?) nephew Farajallāh Khan and grandson, also called Nażar ʿAli Khan, despite deposition from the governorship in 1808, generally supported the Qajars; their cousins and rivals, the khans of Meškin, especially ʿAṭā Khan and his brother Šükür (Šokrallāh) Khan, eventually accommodated the Russian invaders.

For some decades after the Treaty of Turkmanchai (1828) Russia permitted Shahsevan nomads limited access to their former pasturelands in Moḡān, but they failed to observe the limitations. The Russians wished to develop their newly acquired territories, and for this and other more strategic reasons found Shahsevan disorder on the frontier a convenient excuse for bringing moral and political pressure to bear on the Persian government, insisting that they restrain or settle the “lawless” nomads. Persian government policy towards the tribes varied from virtual abdication of authority to predatory punitive expeditions, and an attempt in 1860-61 at wholesale settlement.

The mid-19th century is the first period for which there is any detailed information on Shahsevan tribal society: the main sources are the reports of Russian officials, especially Moḡān frontier Commissioner I. A. Ogranovich and Tabriz Consul-general E. Krebel, though Keith Abbott, British Consul-general in Tabriz, is also informative.

By this time most of the Ardabil tribes, like their elbeys, were already settled. Most of the Meškin tribes, however, despite the brief forced settlement of 1860-61 and the famine and bad winters of 1870-72, remained nomadic; but their elbeys too, especially ʿAṭā Khan’s son Farżi Khan (between 1840 and 1883) and his son ʿAliqoli Khan (1883-1903), had settled bases and soon lost overall control of the nomads. Both elbey families had marriage ties with the Qajar kings, and several members served at court or as military officers.

No longer a unified confederacy with a dynastic central leadership, Shahsevan tribal structure reformed on new principles. Weaker tribes clustered around a new elite of warrior chiefs of the Qojabeyli (notably Nurullāh Bey), ʿIsālu, Ḥāj-ḵojalu and Geyikli tribes in Meškin, and the Polatlı and Yortči in Ardabil. A shifting pattern of rivalries and alliances extended into neighboring regions, involving the powerful chiefs of the Alarlu tribe of Ojarud, the Šatranlu (an offshoot of the Šaqāqi) of Ḵalḵāl, and the Čalabianlu and Ḥāj-ʿAlilu of Qara Dagh.

Russia finally closed the Moḡān frontier to the Shahsevan in 1884. The winter pasturelands in Persia were redistributed among the tribes, but the Moḡān and Ardabil region and the nomads confined there underwent a drastic social and economic upheaval, whose causes were to be found not simply in the closure but also in the behavior of administrative officials. The Shahsevan, numbering over ten-thousand families, were virtually independent of central government for nearly four decades, known as khankhanlıkh or ashrarlıkh, the time of the independent khans or rebels. Although some, such as Moḡānlu, the largest tribe, pursued a pastoral life as best they could, for most nomads life was dominated by insecurity and increasing banditry and vendettas between the warriors of the chiefly retinues.

Russian officials give a detailed and depressing picture of the upheaval, without appreciating or admitting the degree to which their 19th-century rivalry with Britain was responsible for both the frontier situation and the abuses of the Persian administration. V. Markov, concerned only to justify Russian actions and their benefits to the inhabitants of Russian Moḡān, having narrated in detail the events leading up to the closure, does not consider its effects on the Persian side. L. N. Artamonov, however, conducted a military-geographical survey of the region in November 1889, a year after Markov, and was shocked at the poverty and oppression of the peasantry and the obvious distress and disorder suffered by the nomads as a result of the closure. In 1903, Colonel L. F. Tigranov of the Russian General Staff published an informative and perceptive account of the economic and social conditions of the Ardabil province and of the nomad and settled Shahsevan. The detailed reports of Artamonov and Tigranov, although clearly to an extent influenced by political bias, are corroborated by other sources, including accounts recorded by this writer among elderly Shahsevan in the early 1960s.

The Shahsevan reached the heyday of their power and influence in the first decades of the 20th century. They were involved in various important events during the Constitutional Revolution and the years leading to the rise of Reza Shah. In spring 1908, border clashes between Russian frontier guards and Shahsevan tribesmen near Belasovar provided the Russians with a pretext for military intervention in Azerbaijan on a scale that hastened the fall of the Constitutionalist government in Tehran. During the winter of 1908-09, a few Shahsevan joined the Royalist forces besieging Tabriz. In late 1909, while the new nationalist government struggled to establish control of the country, most of the Shahsevan chiefs joined Raḥim Khan Čalabianlu of Qara Dagh and Amir ʿAšāyer Šatranlu of Ḵalḵāl in a union of tribes of eastern Azerbaijan, proclaiming opposition to the Constitution and the intention of marching on Tehran to restore the deposed Moḥammad ʿAli Shah. They plundered Ardabil, receiving wide coverage in the European press, but were defeated soon after by nationalist forces from Tehran under Epʿrem Khan. Subsequent Shahsevan harrying of Russian occupying forces at Ardabil led to a major campaign against them in 1912 by 5,000 troops under General Fidarov, who after many reverses succeeded in rounding up most of the tribes and depriving them of half their property. Despite this catastrophe, remembered in the 1960s as bölgi-yılı, the year of division, Shahsevan warriors continued their guerrilla resistance. During World War I, they were wooed in turn by Russian, Turkish, and British forces. Until the restoration of central government authority under Reza Khan, the Shahsevan chiefs usually controlled the region, pursuing their local ambitions and rivalries, focused on the city of Ardabil and smaller urban centers, and uniting only to oppose Bolshevik incursions in 1920-22. Prominent among the chiefs (those of Ojarud, Qara Dagh, Sarāb, and Ḵalḵāl were now generally talked of as Shahsevan too) were Bahrām Qojabeyli, Amir Aṣlān ʿIsālu, Javād Ḥāj-ḵojalu, Faraj Geyikli, Najafqoli Alarlu, Amir Aršad Ḥāj-ʿAlilu, Naṣrallāh Yortči, Amir ʿAšāyer Šatranlu, and his sister ʿAẓamat Khānom, chief of the Polatlu.

During the winter and spring of 1922-23 the Shahsevan were among the first of the major tribal groups to be pacified and disarmed by Reza Khan’s army. Under the Pahlavis, the tribes were integrated within the new nation-state as equal units under recognized and loyal chiefs. In 1927 the actions of the new gendarmerie provoked a brief revolt, led by Bahrām Qojabeyli. In the mid-1930s, Reza Shah’s brutally enforced settlement of nomads caused considerable economic and social destitution, and was soon abandoned. In 1941, many Shahsevan resumed migrations and revived a loose tribal confederacy, causing trouble to the Soviet occupation forces and the subsequent Democrat regime of 1946.

The disastrous winter of 1948-49 led to a new irrigation scheme in Moḡān, and settlement of the nomads remained an axiom of government policy. From 1960, a series of measures broke down the tribal organization, while pastoralism suffered a sharp decline. The chiefs were dismissed, and the Land Reform not only deprived many chiefs of their power base but nationalized the range-lands and opened them to outsiders. Forced to apply for permits for their traditional pastures, and increasingly using trucks in place of camels for their migrations, the pastoralists were drawn into national and wider economic and political structures. More extensive irrigation works and agro-industrial schemes were inaugurated in Moḡān, which, together with the expansion of farming in the southern highlands, further reduced the pasturelands and increased the rate of settlement.

The revolution of 1978-79 was largely an urban phenomenon. Shahsevan nomads themselves played little part, but settled tribespeople participated in events in towns such as Meškinšahr, Pārsābād, Belasovar and Germi, and in strikes at the Agro-Industry Company in Moḡān. A few former chiefs were killed in these events, others went into exile. As part of the new regime’s rejection of anything to do with monarchy, the Shahsevan were officially renamed Elsevan, “those who love the people (or tribe),” but the new name was not widely accepted and by 1992 it was no longer widely used officially. Pastoral nomadism experienced a modest revival among the Shahsevan, as elsewhere in Iran, such that in the Socio-economic Census of Nomads of 1986 the Shahsevan numbered nearly 6,000 families, as they had in the mid-1960s. At the same time, settlement has continued, following the inexorable spread of various government-supported developments in Moḡān. By the end of the century, Shahsevan pastoral nomadism did not seem likely to survive much longer.

Economic and social organization of the Moḡān Shahsevan. In each alačıq lives a household of, on average, seven to eight people. In the 1960s, groups of three to five closely related nomad households co-operated in an oba, a herding unit that formed a summer camp between June and early September, but joined with others to form a winter camp of ten to fifteen households between November and April. Two or three such winter camps, linked by agnatic ties between the male household heads as a lineage (göbak), would form a tribal section (tira). The section was usually also a community (jamahat/jamāʿat), which moved as a unit during the migrations in May and October, and performed many religious ceremonies jointly. Every group, from herding unit to community, was led by a recognized elder (aq-saqal). The tribe (tayfa), comprising from two to over twenty sections and from fifty to nearly 1,000 households, was a larger community, members of which felt themselves different in subtle ways from members of other tribes. Few contacts, and only one in ten marriages, were made between tribes. In the mid-20th century, the Shahsevan confederacy (el/il) was a loosely organized collection of some forty tribes. After the dismissal of the chiefs, government attempted to deal directly with the sections and their elders, who, as a result, were often younger men, from the wealthiest family in the community, who had the skills and resources to deal with the authorities. But the tribe continued to be important, and remained the main element in Shahsevan identity, nomadic or settled.

Perhaps the most important distinguishing feature of the Shahsevan was their system of grazing rights. Where other nomads operated some type of communal access to grazing, the Shahsevan developed an unusual system whereby individual pastoralists inherited, bought or rented known proportions of the grazing rights to specific named and bounded pastures, although in practice members of a herding unit would exploit their rights jointly. This system was formally invalidated by the nationalization of the pastures in the 1960s, but continued to operate informally at least until the 1990s.

Shahsevan nomads traditionally raised flocks of sheep and goats, the former for milk and milk products, wool, and meat, the latter only in small numbers, mainly as flock leaders. They used camels, donkeys, and horses for transport. Most families raised chickens for eggs and meat, and a few kept cows. Every family had several fierce dogs, to guard the home and the animals against thieves and predators. Bread was their staple food. Some nomads had some settled relatives with whom they cooperated in a dual economy, sharing or exchanging pastoral for agricultural produce. Most, however, sold milk, wool and surplus animals to tradesmen in order to obtain wheat flour and other supplies. Some worked as hired shepherds, paid 5 percent of the animals they tended for every 6-month contract period. Others went to towns and villages seasonally for casual wage-labor. Itinerant peddlers visited most days, but householders went on shopping expeditions to town at least twice a year, e.g. during the migrations. Most purchases were made on credit, against next season’s pastoral produce. The wealthiest nomads raised flocks of sheep commercially, and owned shares in village lands as absentee landlords.

Women too had their elders (aq-birčak, “grey-hairs”), consulted privately by the male elders; among the women the female elders exercised influence in public, at feasts attended by guests from a wide range of communities. At feasts, men and women were segregated. While the men enjoyed music and other entertainment, in the women’s tent the elders discussed matters of importance to both men and women, such as marriage arrangements, disputes, and irregular behavior among community members or broader subjects bearing on economic and political affairs. They formed opinions and made decisions, which were then spread as the women returned home and told their menfolk and friends. This unusual information network among the women served a most important function for the society as a whole.

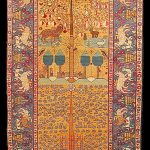

Shahsevan women produced a variety of colorful and intricate flat-woven rugs, storage bags and blankets, and some knotted pile carpets, but these were all for domestic use and figured prominently in girls’ trousseaux on marriage. In the 1970s, however, the international Oriental Carpet trade recognized that a whole category of what had previously been regarded as “Kurdish” or “Caucasian” tribal weavings were in fact made by Shahsevan nomads. Meanwhile, hard times and escalating prices forced many nomads to dispose of items never intended for sale. Since the Islamic Revolution, Shahsevan weavers have increasingly produced for the foreign market, adjusting their styles accordingly.

The Shahsevan of Ḵaraqān and Ḵamsa. In the 19th century there were five major Shahsevan groups in these regions: Ināllu, Baḡdādi, Qortbeyli, Doveyran, and Afšār-Doveyran. The Baḡdādi have traditions of origin in Iraq, while the others, all of Šāmlu or Afšār origins, appear to be descended from groups removed from Moḡān in the 18th century. Most of them were settled by 1900. The Ināllu and Baḡdādi provided important military contingents for the Qajar army (see R. Tapper, 1997, app. 1, pp. 349-55; Ḥasani, 1990; idem, 2002).

Bibliography:

For Shahsevan history, the most comprehensive account, on which this article is based, is Richard Tapper, Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan, Cambridge, 1997; Pers. tr. Ḥasan Asadi, Tāriḵ-e siāsi-ejtemāʿi-e Šāhsevanhā-ye Moḡān, Tehran, 2005; Turk. tr. F. Dilek Özdemir, Iranın Sınır Boylarında Göçebeler; Çahsevenlerin Toplumsal ve Politik Tarihi, Istanbul, 2004.

For an ethnographic analysis, based on field study in the 1960s, see Richard Tapper, Pasture and Politics: Economics, Conflict and Ritual among Shahsevan Nomads of Northwestern Iran, London, 1979.

For women, see Nancy Tapper, “The women’s sub-society among the Shahsevan nomads,” in Lois Beck and Nikki Keddie, eds, Women in the Muslim World, Cambridge, Mass., 1978, pp. 374-98; Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper, “The dress of the Shahsevan tribespeople of Iranian Azerbaijan,” in idem and Bruce Ingham, eds., Languages of Dress in the Middle East, London, 1997.

For human and physical geography of the region, see Günther Schweizer, “Nordost-Azerbaidschan und Shah Sevan-Nomaden”, in Eckart Ehlers, Fred Scholz and Günther Schweizer, Strukturwandlungen im Nomadisch-Bäuerlichen Lebensraum des Orients, Wiesbaden, 1970, pp. 83-148.

On Shahsevan dwellings, see Peter Andrews, “Alachïkh and küme: the felt tents of Azarbaijan”, in Rainer Graefe and Peter Andrews, eds., Geschichte des Konstruierens III (Konzepte SFB 230, Heft 28), Stuttgart, 1987, pp. 49-135.

On Shahsevan textiles, see Jenny Housego, Tribal rugs: an introduction to the weaving of the tribes of Iran, London, 1978; Siyawosch Azadi and Peter Andrews, Mafrash, Berlin, 1985; Parviz Tanavoli, Shahsavan: Iranian rugs and textiles, New York, 1985.

Local histories, valuable for the late 19th and the 20th centuries, include Mir Nabi ‘Aziz-zāda, Tāriḵ-e Dašt-e Moḡān, Tehran, 2005, which reproduces a large collection of documents from both national and family archives of Moḡān and former Shahsevan chiefly families.

See also Ḥosayn Bāyburdi, Tāriḵ-e Arasbārān, Tehran, 1962; Bābā Safari, Ardabil dar goẕargāh-e tāriḵ, 3 vols., Tehran, 1971-83; Nāṣer Daftar-ravāʾi, Ḵāterāt o asnād, ed. Iraj Afšār and Behzād Razzāqi, Tehran, 1984.

Monographs in Persian include Paričehra Šāhsevand-Baḡdādi, Barrasi-e masāʾel-e ejtemāʿi, eqteṣādi o siāsi-e il-e Šāhsevan, Tehran, 1991; Mehdi Mizbān, Il-e Šāhsevan: Mawred-e motaleʿa tāyefa-ye Geyiklu, tira-ye Ḥāji-imānlu, MA thesis, Islamic Free University, Tehran, 1992; Moḥammad-Reżā Begdili, Ilsevanhā (Šāhsevanhā)-ye Irān, Tehran, 1993; Aḥad Nāṣeri-Belasovar, Dašt-e Moḡān dar goẕargāh-e tāriḵ, n.p. ,1993; ʿAtāʾ-Allāh Ḥasani, “Tāriḵča-ye il-e Šāhsevan-e Baḡdādi,” PhD thesis, Islamic Free University, Tehran, 1990.; idem, Farhang-e tāriḵi-e il-e Šāhsevan-e Baḡdādi, Tehran, 2002.

(Richard Tapper)

Originally Published: October 22, 2010

Last Updated: October 22, 2010

![fesenjoun-8490c5929c0547cf4f337dbf5226ce9]](http://iranthisway.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fesenjoun-8490c5929c0547cf4f337dbf5226ce9-683x1024.jpg) 1. Fesenjan (Pomegranate Walnut Stew) This iconic stew, an essential part of every Persian wedding menu, pairs tart pomegranate with chicken or duck. Ground walnuts, pomegranate paste and onions are slowly simmered to make a thick sauce. Sometimes saffron and cinnamon are added, and maybe a pinch of sugar to balance the acid. Fesenjan has a long pedigree. At the ruins of Persepolis, the ancient ritual capital of the Persian Empire, archaeologists found inscribed stone tablets from as far back as 515 B.C., which listed 5/9/2016 Persian Food Primer: 10 Essential Iranian Dishes – Food Republic http://www.foodrepublic.com/2014/10/29/persianfoodprimer10essentialiraniandishes/ 4/9 pantry staples of the early Iranians. They included walnuts, poultry and pomegranate preserves, the key ingredients in fesenjan.

1. Fesenjan (Pomegranate Walnut Stew) This iconic stew, an essential part of every Persian wedding menu, pairs tart pomegranate with chicken or duck. Ground walnuts, pomegranate paste and onions are slowly simmered to make a thick sauce. Sometimes saffron and cinnamon are added, and maybe a pinch of sugar to balance the acid. Fesenjan has a long pedigree. At the ruins of Persepolis, the ancient ritual capital of the Persian Empire, archaeologists found inscribed stone tablets from as far back as 515 B.C., which listed 5/9/2016 Persian Food Primer: 10 Essential Iranian Dishes – Food Republic http://www.foodrepublic.com/2014/10/29/persianfoodprimer10essentialiraniandishes/ 4/9 pantry staples of the early Iranians. They included walnuts, poultry and pomegranate preserves, the key ingredients in fesenjan.