In the nineteen-eighties, when I was a child, my family rarely took vacations. There had been a revolution in Iran, and there was a war on. Most of our trips were to the gardens of family and friends; a couple of times we went to Shomal, as the green band of forests south of the Caspian Sea is known. In those days, travelling was all about us pleasing the group.

We once rented a house by the sea. Everybody had tasks. The women cooked. I was told to keep the frogs and cats away from my paranoid aunt. In the afternoon, when my uncle went jogging, I had to run behind him, carrying a boom box playing “Eye of the Tiger.” He had just returned from the front, and he loved “Rocky.”

That was a rare memory. At home and on trips, we often spent our time hiding from others. We gathered behind walls and inside houses to avoid the sternness of the Islamic Revolution. Public space was no fun: there was always someone disturbing your privacy, making you feel uncomfortable.

Now I look at the youth of today, who are hitchhiking their way through the country, discovering its islands, mountain passes, and changing-color deserts. It took more than three decades for Iranians to venture out once again; now they can’t seem to get enough of it.

Newsha Tavakolian

The New Yorker

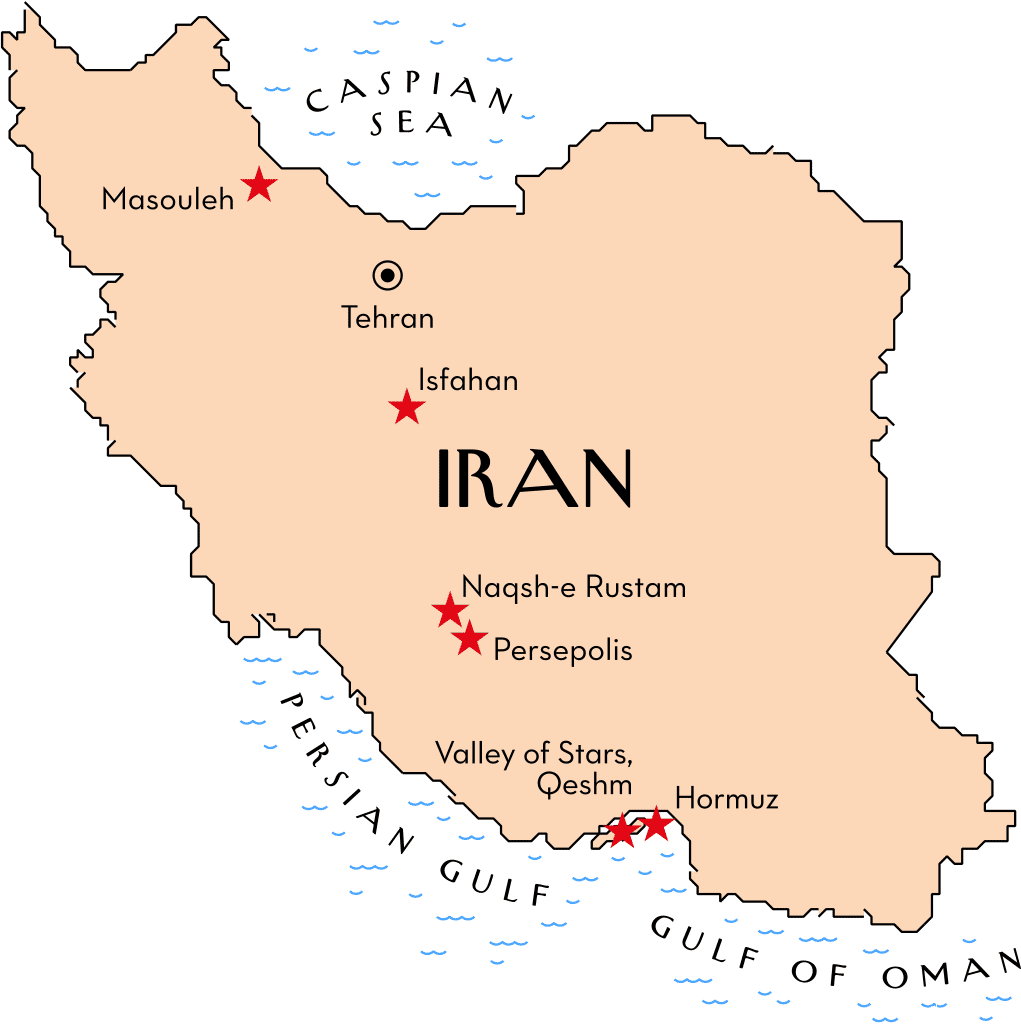

In 330 B.C.E., when Alexander the Great invaded Persia, he destroyed Persepolis. Today, schoolchildren visit the ancient capital and marvel that there was a time when the Persian Empire ruled over much of the world. Photograph by Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum for The New Yorker

A close up of the salt mountains, a part of Hormuz’s diverse geology. Tourists visit the area to marvel at the different colours and shapes of the salt.

A series of carpets laid out to dry after having been washed by professional carpet cleaners, near the royal graves of Naghs-e Rostam, that are carved out in the mountains. They are washing the tapestries for the coming Iranian New Year, that coincides with the Spring equinox, usually on March 21st. The tombs of Iran’s most revered pre-Islamic kings, like Darius, Xerxes and others have been raided long ago, but the reliefs cut out of the mountains’ rocks remain, just as an ancient Zoroastrian fire temple, for tourists to visit.

The Valley of Stars, on the island of Qeshm, was likely formed by prehistoric erosion, though legend holds that it was created by a falling star. Photograph by Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum for The New Yorker

One part of Hormuz island is coral red. The earth is used both for colouring fabrics and make-up. A worker who spends his days gathering up the red soil is waiting during a break.

A driver of a horse and carriage waiting for customers to drive around Isfahan’s Naghshe-Jahan square, or ‘Image of the world’. The city is famous for its Islamic architecture, promoted by the Safavid kings who not only solidified the Shiite faith in Iran, but also enjoyed watching Polo games from the massive balcony of the Ali Qapu palace overlooking the square. The Lotfullah mosque, seen in the background, has been closed for centuries as it was a sacred place for the members of the Shah’s harem but is now open to tourists.

The salt mountains are a part of Hormuz’s diverse geology. Tourists visit the area to marvel at the different colours and shapes of the salt. Mahtab, a tourist from Tehran, is taking a selfie.

The Persian Gulf island Qeshm has a very diverse geology, allowing tourists to visit deserts and mountains and in this case the ‘jungle of Hara’, a mangrove forest. In recent years Iranian tourists have started to discover this and other islands, located in the blue waters of the Persian Gulf. Long secret spots, visited mainly by Iranian hippies and adventurers, the islands are now attracting a wider range of visitors. They come especially in winter when temperatures are cooler and the air is less humid.

Jungle of Hara- qeshm

In the fifth century B.C.E., Persia’s most revered kings were buried in the stone mountain at Naqsh-e Rustam. Robbers have looted the crypts, but tourists still come to see the reliefs cut into the rock. Photograph by Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum for The New Yorker

Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, falls on the spring equinox. In Masouleh, villagers mark the occasion by letting sheep out to graze.

Photograph by Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum for The New Yorker